[INTERVIEW] A little chat with DAVID MACK for his new book HARM'S WAY and STAR TREK

But his work does not stop there, as Mack has written for television (specifically, for two episodes of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine), film and comic books; he also worked as a consultant for the animated television series Star Trek: Lower Decks and Star Trek: Prodigy. In June 2022, he was honoured by the International Association of Media Tie-in Writers with the Faust Award.

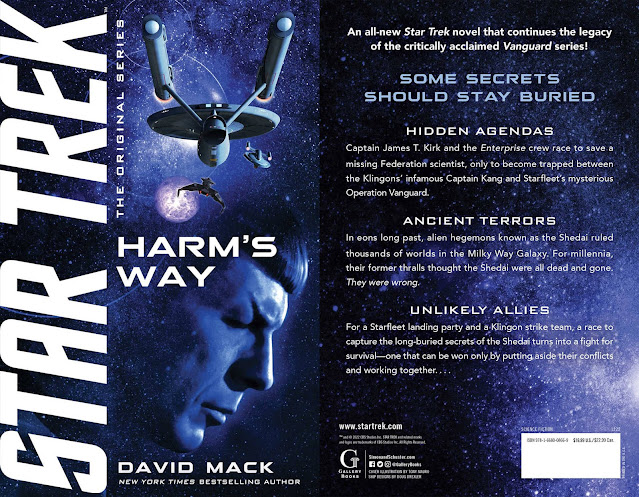

His most recent publications include the short story Fiasco in the complimentary anthology Thrilling Adventure Yarns 2021 and a novel, Oblivion's Gate (Star Trek Coda, Book III); among his forthcoming works there is Harm's Way, a crossover novel between Star Trek: Vanguard and Star Trek: The Original Series, scheduled for release on December, 13th.

And it was precisely on the occasion of this latest Star Trek-themed release that I had the chance to interview David Mack: as a big fan of his novels, I couldn't pass up the opportunity to host on my site one of the authors I appreciate the most within the narrative landscape related to the Star Trek franchise.

Below, the complete interview! If you would like to read it translated into Italian, you can find it HERE.

You have written for many fantasy-related universes (Wolverine, The 4400, Farscape, 24, as well as Star Trek). Which one is your favorite? With a biography of more than thirty titles on Star Trek… could you say Star Trek?

I think it would be fair to say Star Trek remains my favorite, yes. It was my “first love” as a fan, ever since I was old enough to remember. That said, I have found something to enjoy or admire in all of the many franchises for which I’ve written.

What were your first experiences with Star Trek?

I grew up in the early 1970s watching the original Star Trek in syndicated reruns, as well as Star Trek: The Animated Series. I was also an avid reader from a very young age, and some of the first books I ever owned were the numbered collections of James Blish’s Star Trek adaptations.

Just for Star Trek, you’ve written video-game dialogue, comic books, short stories, numerous novels, and two episodes of Deep Space Nine. How do all these experiences differ?

There are so many differences that a complete answer to this question would be very long, indeed. I’ll try to be brief, but I suspect I’ll fail.

Each of these types of writing has their own challenges. Dialogue for video games often means revising or tweaking each line in countless ways, in order to make it fit with any of a number of possible outcomes and scenarios in the game. Sometimes the same information has to be tailored so that it “sounds right” depending upon which character ends up saying it. And it all ends up being done in an Excel spread sheet, which is a peculiar format for a writer.

Comic book scripts aren’t the same as film or television scripts. Instead of describing moving action, a comic book script is written to describe sequences of static images combined with text. Screenplays and teleplays tend to be very spare in their scene descriptions, whereas comic-book scripts can often be extremely detailed, to provide guidance to the artist interpreting it.

Short stories are tricky things. There’s very little time to “get up to speed” as one does with a novel. A short story needs to be focused, precise, and compact, but still feel complete in terms of story logic and emotional payoff. It’s an extremely difficult form to master. I still haven’t. I find writing short fiction very difficult to get right.

Novels are huge, complex beasts. Full of subplots, detours, red herrings, secondary and tertiary arcs. It takes me months to write a novel. Compared to other types of writing, it usually doesn’t pay that well per word, but the rewards come in the form of artistic control over the final product.

Writing for television is faster, by necessity. Writers Guild rules allow for only two weeks to write a commissioned teleplay once the story is agreed upon. And once a TV script or film script is written, it is often rewritten, revised, tinkered with, adjusted, and altered in many different ways by a small army of people, each with their own agenda. Screenwriting is a collaborative art form, and definitely not for writers who are sensitive about seeing others change their words.

You are also a consultant for Star Trek: Lower Decks and Prodigy. Can you tell us, in broad strokes, about your experience and what is your contribution to the two series?

I consulted on the first ten episodes of Lower Decks and on the first twenty episodes of Prodigy.

I was recommended to both shows as a “Star Trek creative consultant.” My role was to find out what the show’s creators and writers wanted to achieve, and then to help them do that in the way most consistent with the preceding 55 years of Star Trek canon content.

When I was being interviewed by the Hageman Brothers for the job at Star Trek: Prodigy, I described my prospective role as that of a “Star Trek sherpa.” My job, I said, was to help the Hagemans and their team scale the narrative summit they wanted to climb, to show them the best Star Trek paths to use, to warn them off of detours that would cost them time or money to fix later, and help them find the best, fastest way to the top of their mountain. And then, when they plant their flag and the photographer snaps the image for history, my job is to stay out of frame.

How do you find working on two highly different series within the Star Trek universe, such as Lower Decks and Prodigy?

Each show has its own personality and its own approach to work flow. It was clear from the outset that the two teams’ different long-term objectives guided their story-telling choices and their approaches to incorporating canon elements into their versions of Star Trek.

Between the animated shows and the live-action programs such as Picard, Discovery, and Strange New Worlds, it has been fascinating to see the breadth of variety in styles and tone that are possible across the span of the Star Trek universe within one production company.

Many of your stories have enormous scope, such as the Destiny trilogy or the Mirror Universe stories and the Vanguard saga. You are also very good at handling small character moments while making them perfectly truthful. How do you strike the right balance between epic, huge storylines and intimate character elements?

My approach to the Star Trek: Destiny trilogy was that even though the overall situation was massive in scope, spanning not just all of the Federation but also its close interstellar neighbors, the moments that readers respond to in a novel format tend to be those about people.

There is spectacle in blowing up a planet, but for it to have an emotional impact we need to experience it through the subjective point of view of someone we are able to understand, and with whom we can empathize. Filtering the tragedy and the terror through the lens of a person’s subjective experience is what makes it feel real for the reader: the characters’ fears, sorrows, and hopes.

This also came into play in the Star Trek: Vanguard saga, though in a different manner. Over the course of roughly nine books, Vanguard tracks the exploration of an ancient alien mystery in the Taurus Reach, while also dramatizing the political maneuverings and machinations of the Klingon Empire, the Romulan Star Empire, and the United Federation of Planets, showing us how this era of tripartite cold-war struggle set the stage for the Star Trek universe we saw in the second through sixth feature films.

But those struggles become meaningful for the reader only once we experience them through the unique perspectives of characters like Diego Reyes, Gorkon, T’Prynn, Tim Pennington, and Cervantes Quinn. It is their personal sacrifices and struggles that give context and meaning to the grand-scale events in which they are embroiled.

Where did the idea for the Vanguard series come from?

Star Trek: Vanguard originated in 2004 with Marco Palmieri, who at that time was one of the editors of Star Trek fiction at Simon & Schuster. He wanted to publish a series set in the era of Star Trek: The Original Series, but with a more modern sensibility, greater emotional and political nuance, and a grander scope.

Some of his key ideas were that the series would be set aboard a starbase on the Federation frontier, and that events in this new literary series would be linked to events seen in the The Original Series, either as predicate causes or as aftereffects. In so doing, it would show that the adventures of the Enterprise crew were influenced by a wider astropolitical arena, and had effects far beyond what we were shown in the 1960s television series.

He hired me to take this core idea and develop it into a full series bible, with long-term story arcs, character bios, and a deep backstory that would tie it into Star Trek’s fictional history and also link it to the events that followed The Original Series. I used it to give added depth to the Tholians, and to provide some backstory for the emergence of the Genesis technology as seen in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

I wrote the first novel, Harbinger, and then I “stacked the deck,” so to speak, to ensure that my friends Dayton Ward & Kevin Dilmore would be hired to write book two. I was so inspired by their new ideas and creative contributions that I persuaded Marco to let me write book three. Marco liked the back-and-forth dynamic that had developed between me on one side and Dayton and Kevin as a writing duo on the other. Consequently, he decided to pursue the rest of Vanguard with us penning alternating books but working as a team to plot the overall story.

Your new Star Trek: The Original Series / Vanguard novel Harm’s Way will be a stand-alone or…?

Yes and no. I wrote Harm’s Way, as I do with any novel, so that someone who has never read any other books in the series can just pick it up, learn what they need to know as they go along, and enjoy the story. This was especially important because, even though it incorporates story elements and characters from the Star Trek: Vanguard saga, Harm’s Way is being published and promoted as a Star Trek: The Original Series novel.

At the same time, for readers who were fans of the Star Trek: Vanguard saga, I wanted this to feel like it could have been written and published as part of that series’s original run. To that end, I researched the chronology of events in The Original Series and the Vanguard saga very carefully. As a result, Harm’s Way is set in July 2266, roughly one week after the events of the Original Series episode The Doomsday Machine, which corresponds to roughly the middle of the fifth Vanguard novel, Precipice.

Can you give us some hints about what we can expect in Harm’s Way?

Thrills, chills, and spills. Action. Adventure. Sarcasm and sentimentality. Heroism and honor. But most of all, I wrote this novel to be fun — an action-packed romp full of snarky banter.

When you have multiple authors writing on a series of novels, how do you coordinate?

We put our trust in an android named Norman, who we simply instruct, “Norman, coordinate.” (For your younger readers who perhaps aren’t as familiar with The Original Series as I am, that was a lame attempt to reference the second-season TOS episode I, Mudd.)

The more serious answer is, “it depends.” (This is, in fact, the most truthful answer to almost all questions about how things get done in publishing.)

On a project like Star Trek: Vanguard, the editor assumes some of the responsibility for keeping details and chronologies straight from one book to the next. However, I built some of that guidance into the series bible for Vanguard. In addition, Dayton, Kevin, and I stayed in regular contact by phone and email through the years while working on the Vanguard saga.

Other multi-author projects, such as the 2013 five-book miniseries The Fall, require extensive pre-planning by our editor, as well as group chats/zoom calls and lengthy email chains by the authors. Because of the need to keep a consistent chronology across five books with overlapping timeframes and difference characters, I built a spreadsheet that broke down the months-long period covered by the minieries into one-day segments. Based on one another’s outlines, I plugged in the data so we could all see exactly what was happening in one another’s stories on any given day within the span of the miniseries. It was a lot of work, but in the end I think we all agreed that it was worth the time it took to create.

What kind of creative freedom do you have when writing a novel for a franchise like Star Trek?More than one might expect, actually. Sometimes, I’ll have a germ of an idea for a story I’d like to write, and I pitch it to the editors. In other cases, the editors will have a need for a novel about a specific series or set of characters, and they will seek out a writer who is both a good fit for the project and available to write it within the limited time available. Either way, the editors expect the authors to conceive original stories that show us something new or unexpected about the characters we already know and like from the shows and movies.

During the period from 2001–2021, those of us writing Star Trek stories set in the 24th-century era, particularly those set after the events of Star Trek: Nemesis, had a lot of freedom to tell stories that altered the status quo of the literary universe. That came to an end with late-24th-century Star Trek’s return to television on Star Trek: Picard.

These days the line is focusing on standalone novels that support the new original Star Trek series being produced for streaming channel Paramount+. But the job of tie-in novelists remains the same: find new original stories to tell that fit within the known parameters of Star Trek canon continuity, and make those stories about people and ideas rather than technobabble.

Also, contrary to what some folks think, the more developed Star Trek’s canon becomes, the easier it is to write new stories within it. Every new detail that enriches the canon offers new possibilities for connecting previously known details, or invites questions that can act as story prompts. Adherence to canon is not an impediment to good storytelling but an inspiration for it.

What do you have in store or coming out besides Star Trek?

Not much, to be honest. At this time I have no new novels in the pipeline, just some short stories that are slated to be part of a number of upcoming anthologies.

Among them are Rough Magic, an original tale that pairs up Shakespeare’s magician Prospero from The Tempest, with Miguel de Cervantes’s deluded knight-errant Don Quixote de la Mancha, for an anthology called Double Trouble; Living by the Sword, a space-western short story; and Bockscar, a World War II-era contemporary fantasy yarn. (Those last two stories are for as-yet-unnanounced short-story anthologies.)

Other than that, I have some spec projects I’ve been tinkering with — among them a new contemporary fantasy novel, an action-comedy Christmas screenplay, and some TV pilots that friends and I have been shopping around. None of them are ready for submission yet, however.

My work as a consultant for Star Trek: Prodigy concluded several months ago, though the fruits of the latter half of that gig are just now arriving on Paramount+. I’m not sure when or if I’ll have the opportunity to work again for Star Trek, on or off the screen, but I’m certainly hoping to tell more tales in that universe in the years to come.

***

You can read the interview with David Mack translated into Italian by CLICKING HERE.

You can purchase David Mack's new novel, Harm's Way, directly from Amazon by CLICKING HERE. You can also retrieve the entire Star Trek: Vanguard series HERE.

Keep an eye on David Mack's website to keep up to date with his future work. You can find it HERE. Also visit his facebook and twitter profiles.

Commenti

Posta un commento